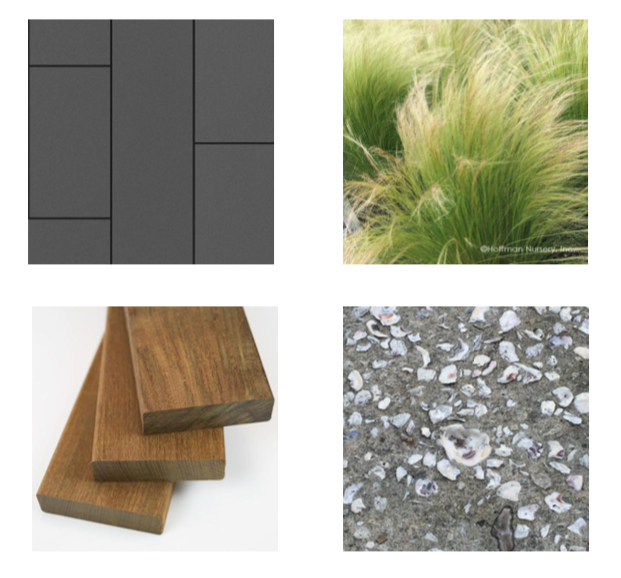

“Neighbors helping neighbors” is a core mission of one of Mount Pleasant’s oldest non-profit organizations. During the start of the pandemic, we had the privilege of assisting East Cooper Community Outreach reorganize their Wellness Pantry to create a safer environment and more efficient layout to better serve the growing client base. This was our first behind-the-scenes glimpse of the work ECCO provides for our East Cooper neighbors. Since then we have been able to learn how each of ECCO’s departments support the core mission and were selected to design the expansion and renovation of their existing facility in Mount Pleasant. Founded as an emergency relief effort in 1989 after Hurricane Hugo’s devastation, East Cooper Community Outreach (ECCO) now functions as a permanent resource for the community through their food pantry, dental, medical, housing and financial assistance services. An over-arching goal of the building improvements was to locate all of the organization’s services under one roof; thus a space needs programming effort was critical to exploring how best to redesign the existing building and add on. The final design provides a total of 16,200sf and a new porte cochere. The existing ‘Lowcountry vernacular’ architectural aesthetic of the existing building was continued in the renovations but with a fresh color scheme to mark this new chapter for ECCO. Click here for an interview with ECCO’s Executive Director, Stephanie Kelley.

A new porte cochere or covered drive will allow clients, volunteers and donors to be protected during daily interactions.

Discussions with staff members resulted in the consolidation of the medical and dental departments to create a single “Health Services” wing (in purple) as well as the importance of consolidating the multiple entrances into a single main entry door where every client is received and personally assisted with their needs.

The existing facility, shown above, was built in 2002 and expanded in 2008.

A Groundbreaking Ceremony was held on April 10, 2024.

General Contractor: Harbor Contracting

Civil Engineering: Seabrook Engineering

Landscape Architecture: The Tomblin Company

Architecture: Rush Dixon Architects

Structural Engineering: ADC Engineering

MPE Engineering: Charleston Engineering

Interior Design: Form + Function